If you're building an AI startup and GTM feels unpredictable, I recently explored why this happens and how trust shapes AI adoption. Now to today’s article here: There is a strange moment that happens after a product stabilizes. Revenue is predictable. From the outside, everything looks aligned. Then, leadership proposes a pilot for a new product or a meaningful evolution of the current one. Immediately, a question surfaces in the room. Are we confused? That question is rarely about the product itself. It is about optics. It is about messaging. It is about whether the market will interpret movement as instability. This is where thoughtful leadership separates itself from reactive leadership. Running pilots after you already have a stabilized product is not a sign of confusion. It is a sign that you understand the difference between clarity and rigidity. However, it remains a sign of strength only if you manage the outreach mechanics and optics with precision. Stability Is Not the Same as Strategic CompletionWhen a product reaches stability, it creates a powerful illusion. The illusion is that the hard thinking is done. In reality, stabilization means you have solved a problem well enough for now. It does not mean you have solved it permanently. Markets evolve. Customer expectations compound. Competitors reposition. Technology lowers barriers. If leadership equates stability with completion, the company slowly shifts from learning mode to protection mode. Protection mode feels responsible. It emphasizes efficiency, cost control, and roadmap discipline. All of that is necessary. However, when protection becomes the dominant instinct, exploration quietly disappears. Pilots are how you prevent that disappearance. They create a structured container for uncertainty. They allow you to test new hypotheses without destabilizing the core. They make learning continuous instead of episodic.

But here is where most companies stumble. They run the pilot. They forget the optics. Where Confusion Actually Comes FromConfusion does not come from experimentation. Confusion comes from an inconsistent narrative. Imagine this scenario. Your outreach team has spent twelve months positioning your company around a single, clear promise. Messaging is tight. Sales decks are aligned. Case studies reinforce one core use case. Then a pilot launches. Suddenly, outbound messages start referencing a new capability. Marketing creates landing pages that hint at a broader vision. Sales representatives are unsure whether to lead with the stabilized product or the experimental one. Customers begin asking a simple question. What exactly do you do?

That is not strategic confusion at the product level. That is executional confusion at the outreach level. The problem is not that you are testing something new. The problem is that you have not separated the pilot narrative from the core narrative. Strong leadership understands that experimentation must be paired with narrative discipline. The Optics of ExpansionMarkets are perceptive. When a company launches a pilot, external observers interpret it through one of two lenses. The first lens is expansion. The company is building on a strong base. It is extending its capabilities in a logical direction. The second lens is a distraction. The company is unsure about its core. It is chasing novelty.

Which lens dominates depends almost entirely on framing. When Amazon launched Amazon Web Services, it did not abandon retail messaging. Retail remained the public anchor. AWS was positioned as a logical extension of internal capabilities. The infrastructure that powered Amazon could power others. When Netflix transitioned from DVDs to streaming, Netflix framed the shift as a natural evolution of delivering entertainment more conveniently. The narrative did not splinter. It compounded. In both cases, the pilot or evolution was anchored to a stable identity. Optics is not about hiding experimentation. They are about sequencing communication. If you communicate pilots as optional extensions rather than existential pivots, markets interpret them as a strength. Outreach Mechanics: The Hidden RiskThe most underestimated risk of running pilots is not product dilution. It is go to market dilution. Outreach mechanics operate on repetition. The market understands you because you repeat the same promise across channels. Sales scripts, website copy, LinkedIn posts, email campaigns, and customer success conversations reinforce one coherent story. When a pilot is introduced without structural separation, repetitive fractures. Sales teams experiment with new positioning mid-conversation. Marketing splits the budget between core campaigns and pilot campaigns. Customer success teams are unsure whether to upsell the pilot or protect satisfaction with the core. Internally, this feels like agility. Externally, it feels like a drift. The solution is architectural, not emotional. Create a dedicated channel for the pilot. Separate messaging tracks. Distinct qualification criteria. Clear language that signals optionality.

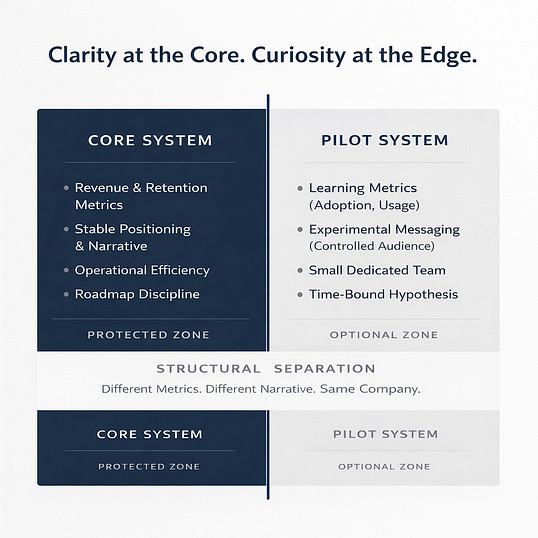

For example, instead of saying, “We are now a platform that does X and Y,” say, “For a small group of customers exploring Y, we are testing an additional capability.” The difference is subtle but powerful. The first statement implies identity change. Confusion is rarely about what you build. It is about how you narrate what you build. Clarity at the Core, Curiosity at the EdgeA stabilized product represents clarity at the core. Pilots represent curiosity at the edge. When leaders blur those boundaries, teams feel tension. They do not know which KPI takes priority. They do not know which narrative to amplify. They oscillate between defending the existing roadmap and chasing the new idea. When leaders define those boundaries explicitly, tension transforms into energy. The core has protected metrics. Revenue, retention, operational excellence. The pilot has learning metrics. Adoption rates, usage patterns, and qualitative feedback. The core has standardized messaging. This separation prevents the psychological whiplash that often masquerades as strategic confusion. It tells the organization, “We are not unsure about who we are. We are disciplined about who we are becoming.” Customers Do Not Fear Evolution. They Fear Instability.There is another myth that holds leaders back from running pilots. The myth is that customers crave stasis. In reality, customers expect iteration. They use products from companies like Apple Inc., where ecosystems expand continuously. New services appear. Features evolve. The core experience remains stable. Customers rarely object to thoughtful evolution. They object to broken promises. If your stabilized product continues to deliver on its core promise, a pilot does not feel like abandonment. It feels like an investment in the future. However, if resources visibly shift away from maintaining quality in the core, customers infer instability. The lesson is straightforward. Do not fund pilots by starving the foundation. Strength is visible when the existing product continues to improve even as new ideas are tested. Financial Discipline Is a Signaling ToolLeaders sometimes hide behind financial caution to avoid experimentation. Why allocate resources to a pilot when the core product is delivering predictable returns? The real question is how you allocate, not whether you allocate. Pilots should be proportionate. Small teams. Defined budgets. Clear timelines. Explicit exit criteria. When stakeholders see discipline around experimentation, they interpret pilots as intentional rather than impulsive. When pilots expand without guardrails, the narrative shifts toward confusion. Financial structure is part of optics. It communicates that leadership is curious but not reckless. The Compounding Advantage of Structured ExperimentationA single pilot may fail. Two pilots may stall. Three pilots may never reach scale. If you evaluate them in isolation, they appear wasteful. If you evaluate them as a system, they become a compounding engine of insight. Each pilot teaches you about customer willingness to pay. Each test reveals friction in distribution. Each experiment refines positioning. Even when the feature is sunset, the learning migrates back to the core. Over time, this creates strategic optionality. Companies that normalize pilots become faster at interpreting change. They reduce emotional attachment to any one roadmap. They develop internal muscle memory around iteration. When a genuine inflection point arrives, they are prepared. Organizations that avoid pilots to preserve optics often discover change only after revenue declines. At that point, confusion is real. The Leadership Question Beneath the StrategyAt its core, this debate is about leadership identity. Do you want to be the leader who protects what works until it erodes? Or the leader who uses stability as a platform for controlled evolution? Running pilots after achieving product market fit is not about chasing trends. It is about acknowledging that relevance decays unless refreshed. However, running pilots without narrative discipline creates unnecessary noise. Strength is not experimentation alone. It is the ability to say, with conviction, “This is who we are today,” while also saying, “This is what we are testing for tomorrow.” It is maintaining clarity in outreach while expanding the capability in product. It is protecting the core without worshiping it. When done well, pilots do not dilute identity. They deepen it. They demonstrate that your company is confident enough to learn in public, disciplined enough to separate signal from noise, and mature enough to evolve without panic. That is not confusion. That is strategic composure under changing conditions. And in modern markets, composure is one of the rarest forms of strength. - Have early traction but an unclear revenue signal? One-Week Market Signal Test ($30) Validate demand. Decide with proof. |

Entrepreneur Examples

Monday, March 9, 2026

Pilots After Product Market Fit

Monday, March 2, 2026

The Anti-Fragile Startup: Building Business That Get Stronger When Things Break

The Anti-Fragile Startup: Building Business That Get Stronger When Things BreakWhy stability is often the most dangerous illusion in modern business, and how volatility, properly structured, becomes an advantage

Stability Is Often a Precursor to CollapseThe most dangerous systems are not always those under visible stress. They are often the ones who appear calm. Extended periods of stability change behavior. Risk feels distant. Safeguards are relaxed. Leverage increases. Margins of safety narrow. The absence of disruption becomes interpreted as proof that disruption has been eliminated.

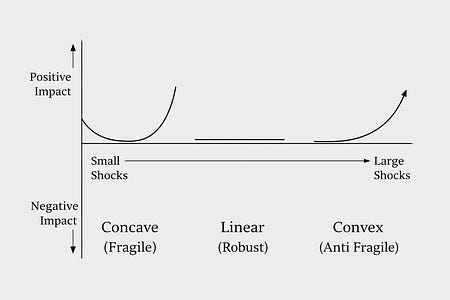

His insight was structural, not metaphorical. When markets experience long stretches of predictable growth, participants increase leverage because recent history suggests they can. Debt expands. Complexity deepens. Interdependence grows. The system appears strong precisely because its vulnerabilities are not being tested. The collapse of Lehman Brothers in 2008 illustrates the pattern. For years, Lehman accumulated large positions in mortgage-backed securities and financed them with borrowed money. As long as housing prices rose steadily, profits reinforced the perception of soundness. The structure held under ordinary conditions. But leverage introduces nonlinearity. When housing prices began to fall, losses were amplified across the firm’s balance sheet. Because Lehman had relatively little equity compared to its obligations, modest market stress translated into existential pressure. What appeared stable under one regime proved fatally exposed under another. The fragility had not been visible during calm. It had been embedded in the structure. History offers similar lessons outside finance. In the 1840s, Ireland relied heavily on a genetically uniform potato crop. When potato blight spread, the lack of genetic diversity meant there was no natural buffer. A plant disease became a national catastrophe. Uniformity had maximized output under normal conditions. It eliminated resilience under stress. In 1986, the Space Shuttle Challenger disintegrated shortly after launch because O-ring seals in the solid rocket boosters failed in unusually cold temperatures. The seals had shown vulnerability in previous launches. Under typical conditions, they performed adequately. Under edge conditions, the weakness became catastrophic. In each case, collapse was not caused by constant chaos. It was caused by structures optimized for normal conditions without sufficient tolerance for variation. Stability can conceal accumulated risk. Calm can be a warning sign. Fragile, Robust, and Anti-FragileIt was in response to this blindness toward hidden exposure that Nassim Nicholas Taleb introduced a third category in Antifragile. We are familiar with fragility. Fragile systems are harmed by volatility. A porcelain glass shatters when dropped. A highly leveraged firm collapses when asset prices decline. The defining characteristic is asymmetry. Small shocks cause disproportionately large damage. We also understand robustness. A robust system resists disturbance. A well-capitalized institution survives a recession. A steel beam withstands load without bending. Robustness is strength under stress, but it is neutral. The system endures. It does not improve. Taleb’s contribution was to identify something different.

Anti-fragile systems require variability. They improve because of stressors, randomness, and disorder. The human body offers a simple illustration. Muscles grow stronger through resistance training. Controlled micro damage triggers repair and adaptation. The immune system strengthens through exposure to pathogens. Evolution itself depends on variation and selection. Without mutation, adaptation stalls. The distinction lies in the response to volatility. Fragile systems experience negative asymmetry. Harm increases faster than benefit. Robust systems experience symmetry. Stress produces little net change. Anti-fragile systems experience positive asymmetry. Small stressors generate improvement.

The same external force destroys one structure and strengthens another. The difference lies not in the wind but in the design of the system. Most modern institutions are engineered for efficiency and predictability. They function exceptionally well when conditions remain within expected bounds. The difficulty is that real-world systems rarely remain within bounds. Volatility is not the exception. It is the rule. Economic Systems and the Accumulation of Hidden FragilityFragility does not emerge only in isolated institutions. It accumulates across systems. Modern economies reward efficiency. Capital is allocated toward optimization. Supply chains are streamlined. Redundancy is treated as waste. Slack is eliminated in the name of productivity. Under stable conditions, this produces impressive results. Margins expand. Output increases. Costs decline. The system appears intelligent because it functions smoothly. Yet efficiency often removes the very buffers that absorb stress. Global supply chains before the COVID pandemic provide a clear illustration. Just-in-time manufacturing minimized inventory and reduced storage costs across industries. Firms depended on precisely timed shipments that crossed continents. Under normal conditions, the system operated with remarkable precision. When transportation halted and factories shut down, minor disruptions cascaded globally. A shortage of semiconductors slowed automobile production. Delays in one port created ripple effects across entire sectors. The structure had been optimized for cost, not variability. The vulnerability was not visible during calm. It was structural. The same pattern appears in energy markets. Countries dependent on a single dominant supplier enjoy predictable pricing during peaceful periods. When geopolitical tension interrupts supply, the absence of diversification becomes strategic exposure. Systems that suppress volatility often accumulate fragility silently. Risk is not removed. It is deferred. This is why Taleb repeatedly warns against the illusion of control. Complex systems cannot be fully predicted. Attempts to smooth them completely often amplify future instability. The issue is not whether shocks will occur. It is whether the structure absorbs them gradually or collapses abruptly.

When Volatility Becomes a TeacherIf fragility describes disproportionate harm under stress, anti-fragile systems display the opposite pattern. They convert disorder into information. This dynamic can be observed in competitive markets. During the early months of the COVID crisis, many firms froze activity in response to uncertainty. Others treated the disruption as feedback. Consumer behavior shifted rapidly toward digital services. Companies that experimented quickly with new channels, pricing models, or delivery formats gathered data at high velocity. Volatility revealed weak assumptions and surfaced unmet demand. The video communications platform Zoom provides a useful example. When global usage surged, the platform experienced scrutiny over security vulnerabilities. Public criticism intensified. Rather than deflecting, founder Eric Yuan acknowledged shortcomings and redirected engineering resources toward strengthening encryption and privacy controls. Stress exposed weaknesses that might have remained secondary concerns in slower conditions. The organization adapted under pressure. Similarly, after rapid pandemic-driven expansion, Shopify faced a reversal in growth momentum. Leadership responded with restructuring and renewed focus on core merchant services. The adjustment was painful, but it clarified strategic priorities. In both cases, volatility did not merely threaten survival. It forced reassessment. It accelerated learning.

Pain without reflection leads to collapse. Reflection without exposure produces stagnation. Anti-fragility requires both. The defining question for any organization is not whether it encounters stress. It is how the structure processes it. Does pressure reveal information that strengthens the system, or does it trigger cascading breakdown? Volatility is constant. The asymmetry of response determines the outcome. The Company as a Volatility Processing SystemA company can be understood as a structure that processes uncertainty. Revenue fluctuates. Costs fluctuate. Regulation shifts. Technology evolves. Consumer behavior drifts. Every organization exists in moving conditions. The question is not whether external shocks occur. It is how internal architecture responds to them. Some firms are tightly coupled systems. Decision-making is centralized. Revenue depends heavily on a single product line or channel. Costs are calibrated to current demand. Margins leave little room for error. Under stable conditions, this design produces efficiency and clarity. Under stress, it magnifies exposure. Highly leveraged firms illustrate this clearly. During periods of rising asset prices, debt amplifies returns. When prices decline, the same leverage accelerates losses. The structure that rewarded optimism punishes reversal. The same structural principle appears in platform dependency. Early in its growth, Zynga relied heavily on distribution through Facebook. As long as platform algorithms favored social gaming, user acquisition scaled rapidly. When platform policies shifted, growth contracted sharply. The internal product did not fail overnight. The external dependency introduced asymmetry. Fragility often hides inside concentration. By contrast, firms that distribute exposure across products, geographies, suppliers, and revenue models tend to experience smaller localized failures rather than systemic collapse. Diversity reduces the chance that one shock becomes existential. Consider Atlassian. For much of its history, Atlassian relied on product-led growth rather than a large enterprise sales force. Its distribution model reduced dependence on high fixed sales overhead. This did not eliminate risk. It altered the shape of risk. Lower structural fixed costs meant that downturns did not automatically trigger unsustainable burn. Anti-fragility does not imply immunity. It alters how stress propagates through the system. In tightly coupled structures, stress travels quickly and amplifies. In modular structures, stress is compartmentalized and informative. Optionality and the Preservation of Convex OutcomesTaleb frequently uses the language of convexity to describe anti-fragile systems. Convexity refers to payoff asymmetry. Losses are limited. Gains can expand. In practical terms, convex systems survive small errors while remaining exposed to large positive surprises. One way organizations create convexity is through optionality. Optionality preserves the ability to change direction without catastrophic cost. The marketing platform Mailchimp offers a useful example. For decades, the company operated without venture capital funding. This choice limited growth speed but preserved independence. Without the pressure of external capital cycles, strategic decisions were not constrained by fundraising timelines or investor mandates. When Intuit acquired Mailchimp in 2021 for approximately 12 billion dollars, the outcome was not the result of hyper-leveraged expansion. It was the product of sustained profitability and retained choice. Optionality increases the range of possible favorable outcomes while containing downside exposure. This principle also applies to experimentation. Small-scale trials allow organizations to test new markets or products without risking core stability. If the experiment fails, the loss is bounded. If it succeeds, the upside can scale. Anti-fragile structures tend to favor many small, reversible decisions over a few large irreversible bets. The goal is not constant disruption. It is controlled exposure. Convex systems welcome variation because they are positioned to gain more from favorable deviations than they lose from unfavorable ones. The alternative is concavity. In concave structures, the upside is capped while the downside expands rapidly. Highly leveraged expansions, single-channel dependence, or narrow product concentration often create this profile. The distinction between convex and concave exposure rarely appears during stable periods. It becomes visible when conditions shift. Volatility does not create structure. It reveals it. Taleb sharpens this idea further when he writes:

Leadership Under Stress and the Human VariableStructures do not operate independently of the people who guide them. Even well-designed systems can become fragile when leadership interprets volatility as personal failure rather than structural feedback. Stress reveals assumptions. It also reveals the ego. When growth slows or public sentiment shifts, leaders often face a psychological fork. One path seeks denial, external blame, or defensive escalation. The other path treats volatility as diagnostic. Reflection converts disorder into learning. Without reflection, pain compounds without insight. Corporate history offers multiple examples of leaders who treated volatility as a signal rather than a threat to identity. During the post-pandemic slowdown, Shopify recalibrated after overexpansion. Leadership publicly acknowledged misjudgments about the permanence of pandemic-driven demand and refocused on core merchant tools. The admission was uncomfortable. It was also adaptive. The capacity to detach the ego from the strategy becomes a structural variable. In rigid leadership cultures, negative feedback is suppressed. Teams optimize reporting upward rather than adapting outward. Small problems remain unaddressed until they accumulate into large failures. In reflective cultures, friction surfaces earlier. Dissent is tolerated. Weak signals are examined rather than dismissed. This allows incremental correction before volatility escalates into a crisis. Anti-fragile organizations are rarely loud about their adaptability. They simply adjust faster than their environment deteriorates. Psychological rigidity can render even financially sound institutions vulnerable. Intellectual humility, by contrast, introduces elasticity into decision making. The human layer is not separate from structure. It is part of it. The Acceleration Problem in the Age of AIThe current technological environment compresses cycles dramatically. The rise of generative models from firms such as OpenAI has reduced the time required to build, prototype, and deploy new products. Barriers to entry fall. Iteration speeds increase. Competitive landscapes shift within months rather than years. Acceleration amplifies exposure. When product differentiation erodes quickly, companies built on narrow advantages face rapid commoditization. When tools are widely accessible, defensibility shifts from technology to distribution, trust, and adaptability. Volatility increases not only because markets fluctuate, but because innovation itself accelerates. This environment intensifies the cost of structural fragility. Heavy fixed investments in a single technical architecture may become obsolete quickly. Overreliance on a single model provider introduces platform risk. Excess hiring during expansion cycles becomes difficult to unwind when momentum slows. At the same time, acceleration enhances the potential for anti-fragility. Faster feedback loops mean assumptions can be tested rapidly. Small-scale experiments can generate insight within weeks. Companies that treat technological change as continuous input rather than episodic disruption can refine more quickly than competitors anchored to previous models. The compression of time increases both downside and upside asymmetry. In slow environments, fragility unfolds gradually. In fast environments, it is exposed almost immediately. The decisive variable is structural flexibility. Organizations that preserve optionality, diversify exposure, and maintain adaptive leadership can metabolize acceleration as information rather than as a threat. Technology does not create fragility or anti-fragility. It magnifies what is already present. Optimization Culture Versus Exposure CultureMuch of modern management thinking is built around optimization. Optimize for margin. Optimization assumes stable constraints. It assumes that yesterday’s variables will persist long enough for fine-tuning to matter. Under those conditions, efficiency is rewarded. But optimization often narrows tolerance. When systems are tuned tightly to current conditions, small deviations produce disproportionate strain. Buffers are removed because they appear unnecessary. Redundancy is eliminated because it appears inefficient. Slack is treated as waste rather than protection. This logic works in linear environments. It fails in nonlinear ones. Anti-fragility requires a different orientation. It is less concerned with perfect calibration and more concerned with survivability under variation. It accepts small losses as the price of long-term durability. It favors modularity over tight coupling. It privileges optionality over precision. Optimization culture asks, “How do we maximize output under these conditions?” Exposure culture asks, “What happens if these conditions change?” The difference is philosophical. One worldview assumes stability and treats volatility as an interruption. The other assumes volatility and treats stability as temporary. The anti-fragile organization does not attempt to eliminate randomness. It structures itself so that randomness is more likely to generate insight than ruin. This shift in posture is subtle but profound. It changes hiring decisions, capital allocation, supplier relationships, and product design. It changes how leaders interpret negative feedback. It changes how success is measured. A fragile system becomes brittle because it believes the world is predictable. An anti-fragile system remains adaptive because it assumes the opposite. Designing for DisorderVolatility is not an anomaly in economic life. It is a permanent feature. Technological disruption, geopolitical shifts, capital cycles, regulatory change, and cultural evolution ensure that no equilibrium persists indefinitely. Attempts to engineer permanent calm often postpone and intensify eventual disruption. The anti-fragile company does not romanticize chaos. It does not pursue reckless exposure. It acknowledges limits. It bounds downside risk. It preserves room to maneuver. Most importantly, it learns faster than conditions deteriorate. This is ultimately the defining characteristic. In fragile systems, stress accumulates silently until failure is abrupt. In anti-fragile systems, stress is surfaced early and integrated incrementally. The difference is temporal. Fragile systems postpone feedback. Taleb’s insight remains deceptively simple. Some structures are harmed by volatility. Others gain from it. The question is not whether disruption will occur, but whether it will reveal weakness or produce adaptation. In complex environments, permanence is an illusion. Endurance belongs not to the largest, nor to the most optimized, but to those designed with humility toward uncertainty. The anti-fragile startup is not built for smooth quarters. It is built for the moment when smoothness ends. And in a world defined by acceleration, that moment always arrives. - Have early traction but an unclear revenue signal? One-Week Market Signal Test ($30) Validate demand. Decide with proof. © 2026 Startup-Side |

Pilots After Product Market Fit

Running new product pilots after stabilization can either signal strength or create confusion. This deep dive explains how to structure expl...

-

Crypto Breaking News posted: "Mikhail Fedorov, Ukraine's Deputy Prime Minister and the head of the country's Minist...

-

Techie.Buzz posted: " [ANN] Serverless Kubernetes Solution For Cloud-Native Apps by CTO.ai CTO.ai is a provider of deve...

-

kyungho0128 posted: "China's crackdown on Bitcoin (BTC) mining due to energy consumption concerns is widely regarded as...