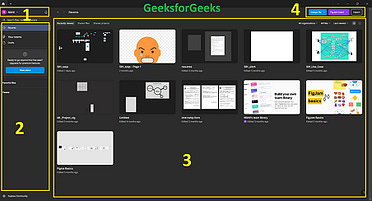

If your validation can’t disprove the idea, it’s not validation.Why validation often protects the wrong beliefs and how founders pay for it laterWhen Doing Everything Right Still Goes WrongFor a long time, BlackBerry was doing exactly what serious companies are told to do. They listened to their best customers. Enterprise clients renewed contracts. Governments trusted their security. Power users typed thousands of emails a week on physical keyboards that were objectively faster than touchscreens. Internally, decisions were grounded in metrics that had worked for years: reliability, encryption, battery life, and administrative control. When touchscreen phones started gaining attention, BlackBerry didn’t ignore them. They evaluated them. And by BlackBerry’s standards, they were worse. Slower to type on. Less secure. Less suited for people who live in email all day. There was nothing reckless about staying the course. Around the same period, Boeing found itself under a different kind of pressure. Airlines wanted better fuel efficiency. Competitors were moving fast. Timelines mattered. Boeing introduced a new automated control system into an existing aircraft design and ran it through established certification processes. Simulators were used. Failure modes were reviewed. Pilot training requirements were evaluated. Each step produced the same outcome: trained pilots could recognize the system’s behavior and respond correctly. The documentation was complete. The reviews were formal. The approvals were granted. Again, nothing about this looked careless. In both cases, the people involved believed they were doing the right thing. They weren’t guessing. They weren’t ignoring warning signs. They were following the process, relying on data, and validating decisions the way competent organizations are supposed to. At the time, there was no obvious reason to think something important was being missed. That only became clear later. What is happening at the core human level when this occursWhen cases like BlackBerry or Boeing are discussed after the fact, they are often framed as failures of judgment or vision. That framing is comforting because it suggests the problem was a lack of intelligence or courage. But that is rarely what is actually happening. At the human level, this pattern has very little to do with competence. It is driven by a much deeper instinct about how we decide what is true. Humans have a strong tendency to confuse coherence with correctness. When a belief fits the data we already have, aligns with past success, survives structured review, and feels internally consistent, it acquires a sense of solidity. It stops feeling provisional. It starts feeling real. Not in a philosophical sense, but in a practical one. It feels safe enough to act on. At that point, validation quietly changes its role. Instead of being a way to surface uncertainty, it becomes a way to manage discomfort. It reduces anxiety by showing that the decision is defensible. It justifies commitment by demonstrating that due process was followed. It legitimizes action by making it feel earned rather than impulsive. None of this is usually conscious. People do not sit in rooms thinking about protecting beliefs. They think they are being careful. Responsible. Methodical. But the outcome is that validation systems are shaped less by what could disprove a belief and more by what makes that belief feel stable enough to proceed. They are designed to feel rigorous and look comprehensive while quietly preserving the assumption they are meant to test. That is why these failures are so hard to see from the inside. The process is doing exactly what it is psychologically rewarded to do. The science underneathFrom a cognitive and neurological perspective, this behavior is not surprising. The human brain is optimized for action under uncertainty, not for eliminating uncertainty. Large parts of the prefrontal cortex are devoted to integrating incomplete information into coherent models that can guide decisions. This makes humans exceptionally good at pattern completion, narrative construction, and explaining outcomes after the fact.

Once a belief has formed, the brain tends to treat it as a working model rather than a hypothesis. New information is filtered through it. Evidence that fits is easier to encode and recall. Evidence that conflicts are more effortful to process and easier to dismiss as noise or an exception. This is not a flaw in the moral sense. It is an efficiency mechanism. Maintaining multiple competing interpretations of reality is metabolically expensive. Actively trying to falsify beliefs threatens more than correctness. It threatens identity, competence, and status. It forces people to confront the possibility that their prior reasoning, expertise, or judgment may not generalize as well as they thought. As a result, unless a system is explicitly designed to force disconfirmation, the brain will naturally drift toward belief protection. It will seek closure, coherence, and justification long before it seeks falsification.

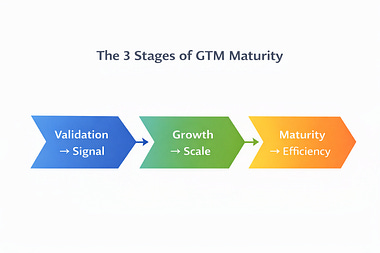

This is why simply telling people to “be more objective” or “challenge assumptions” rarely works. The default cognitive machinery is working against that goal. Without structural pressure, validation will almost always converge toward reassurance rather than exposure. Why this matters for foundersFounders operate in environments where uncertainty is not a phase but a constant. Feedback arrives late, often distorted by politeness or noise. The consequences of being wrong are asymmetric. Small mistakes compound quietly, while correct decisions rarely announce themselves until much later. This is all the more relevant for the first GTM stage i.e validaiton phase. In that setting, validation feels like a form of discipline. It is a way to slow down impulse, to avoid self-deception, to show that a decision is grounded rather than imagined. Most founders are not trying to be reckless. They validate precisely because they are trying to be careful. The problem is not the intent. It is what validation gradually turns into. Instead of being a way to surface what might be wrong, validation often becomes a way to earn the right to move forward. It functions as a permission structure. A signal that enough boxes have been checked. A mechanism for generating confidence that feels earned rather than assumed. At that point, validation stops being about truth and starts being about justification. It reassures teams. It calms investors. It allows founders to commit without feeling irresponsible. And because it feels responsible, it is rarely questioned. This is what makes founders especially vulnerable. In an environment where action is required before certainty is possible, validation quietly shifts from a tool for exposing fragility into a moral license to proceed. The more uncertain the terrain, the more tempting that shift becomes. When founders did it wrong at validation phaseIn 2011, Bill Nguyen had reason to be confident. He had raised tens of millions of dollars for Color, backed by some of the most respected investors in Silicon Valley. The technology worked. Photos appeared instantly on nearby phones, grouped automatically, without anyone having to add friends or curate feeds. When Nguyen showed the product, people nodded. They got it. Engineers admired the architecture. Investors praised the ambition. In the weeks before launch, validation looked positive. People said photo sharing was important. They said the experience felt magical. They said the idea was interesting. What no one asked was what it would take for someone to actually use it on a Tuesday afternoon. Using Color meant opening a new app instead of the ones people already checked habitually. It meant trusting an unfamiliar social context. It meant changing how moments were captured and shared, without any immediate pull from existing relationships. None of that surfaced during validation, because validation never forced users to make a tradeoff. It asked whether the idea made sense, not whether it would displace behavior that was already working. When Color launched, people did not reject it. They simply didn’t reorganize their habits around it. The idea survived the explanation. It did not survive indifference. Validation had confirmed that the concept was reasonable. It had never tested whether behavior would actually change when there was friction, choice, and no one watching. A decade earlier, a similar pattern played out with Webvan, founded by Louis Borders. On paper, Webvan looked inevitable. Customers wanted groceries delivered. Surveys said so. Market research supported it. Early pilots showed interest. The logic was clean: groceries were a frequent, universal need, and delivery would save time. Borders validated aggressively and expanded fast, building infrastructure ahead of demand to meet what seemed like an obvious future. But grocery shopping is not just a transaction. It is a habit, embedded in routines, price sensitivity, and trust built over the years. Using Webvan required customers to plan differently, pay differently, and give up control over selection and timing. Those costs were small individually, but cumulative in practice. Validation never forced those costs into view. It confirmed that delivery sounded appealing. It did not test whether people would consistently alter their weekly behavior enough to support the economics required to make the model work. When reality arrived, interest was not the problem. Inertia was. In both stories, the founders did what they believed responsible founders should do. They validated demand. They gathered feedback. They built coherent narratives around why adoption would follow. What they validated was reasonableness. Startups do not fail because ideas are unreasonable. They fail because behavior does not move. Habits dominate attention. Existing workflows resist replacement. Constraints assert themselves quietly and persistently. Validation that does not force people to pay a real cost in time, effort, money, or discomfort cannot reveal whether a product will actually live in the world. It can only show that the idea sounds good while nothing is at stake. That is not product validation. It is plausibility testing. What happens when founders do it rightWhen Dylan Field started working on what would become Figma, the idea itself was easy to dismiss. Serious design tools lived on desktops. They were heavy, powerful, and local. Browsers were slow, unreliable, and not where professionals did real work. Field’s belief cut directly against that norm. He thought designers would accept a browser-based tool if collaboration became immediate and friction disappeared. It was a fragile belief. Years of habit stood against it. So he did not ask designers what they thought. He built a minimal browser-based editor and invited a small group to use it for actual projects. No promises. No migration paths. No safety net. If designers treated it as a curiosity and returned to their desktop tools, the belief would end there. Some did. But enough designers stayed. They shared links instead of files. They edited together in real time. They did work that mattered inside a tool that was not supposed to support it. They did not argue that it could work. They simply worked. The belief survived because behavior changed, not because the idea sounded convincing. Years earlier, something similar happened with Shopify, though in a very different domain. Tobi Lütke did not start Shopify to build a platform. He started it to run his own online store. The belief forming quietly behind the tool was specific and testable: non-technical merchants would set up and operate online stores themselves if the software removed enough friction. That belief could not survive explanation alone. So Lütke released the tool and watched what happened. Did merchants configure stores on their own? Did they list products? Did they accept payments? Did they launch without help? If every store required hand-holding, the belief would collapse quickly. Many did not. Merchants signed up, configured storefronts, and started selling without talking to anyone. Not because they were persuaded, but because the cost of trying was low and the payoff was immediate. The software either fit into their behavior or it didn’t. In enough cases, it did. What these stories share is not luck or foresight. It is how validation was framed at the very first point of contact with the market. In both cases, the founders created situations where being wrong would be cheap and obvious. Beliefs were exposed to real behavior early, before confidence hardened into identity. Validation did not provide reassurance. It replaced it with information. When a belief survives an honest attempt to disprove it, it earns strength. This is what real validation looks like at GTM stage one. Where Validation Breaks DownWhat makes this kind of validation hard is not ignorance but pressure. Early on, belief holds everything together. It aligns teams, reassures investors, and creates momentum before there is much evidence to lean on. Tests that can fail threaten that belief at the exact moment it feels most necessary. There is also an emotional cost. Early disproof feels less like learning and more like personal failure. Founders are deeply identified with their ideas, and environments around them reward confidence, not uncertainty. As a result, validation quietly shifts from exposing fragility to protecting morale and legitimacy. That is why this is not a methodological problem but a philosophical one. Founders who do this well stop asking whether an idea sounds right and start asking what would make it wrong. They design tests that can falsify beliefs and treat belief death as progress. The goal is not reassurance. It is removing wrongness before reality does it for you. - Before you build anything, make sure someone wants it enough to pay. I put together a free 7-day email course on revenue-first customer discovery — how to pull real buying intent from real conversations (without guessing, overbuilding, or hoping). If you’re a builder who wants clarity before code: |

Monday, January 26, 2026

If your validation can’t disprove the idea, it’s not validation.

Monday, January 19, 2026

Cultural Gravity: How Constraints Become Distribution Advantages

Cultural Gravity: How Constraints Become Distribution AdvantagesFour Markets. Four Decisions. Four Different Definitions of “Doing It Right.”

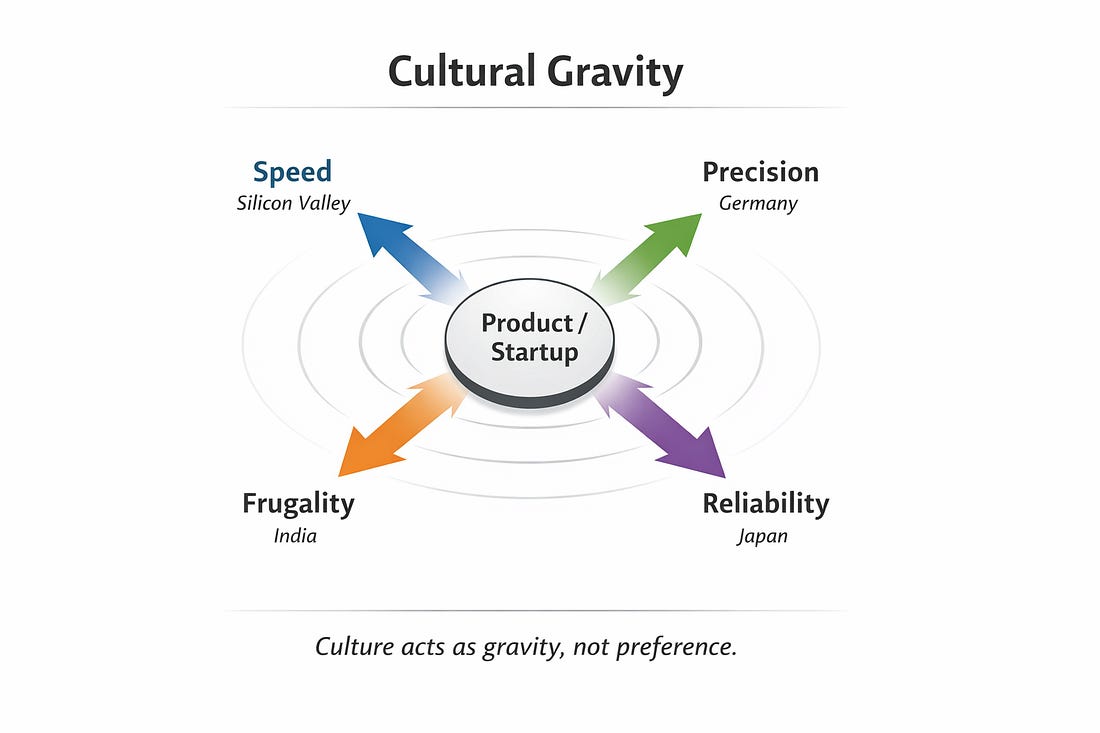

In the mid-2000s, Facebook shipped products faster than most companies could hold internal reviews. Features launched half-finished. In many markets, this behavior would have destroyed trust. In Silicon Valley, it accelerated dominance. Speed wasn’t just tolerated - it was admired. Shipping imperfectly signaled ambition. Waiting signaled fear. Early users didn’t ask whether the product was complete; they asked whether it was moving. Speed itself became a trust signal. The product didn’t succeed despite its rough edges. In another continent, when Walmart entered Germany, it brought scale, operational excellence, and aggressive pricing - the same playbook that had dominated the U.S. On paper, it should have worked. Instead, it failed. Not because prices were wrong. Walmart violated deep expectations around professionalism, labor relations, authenticity, and rule-based competition. Excessive friendliness felt insincere. Speed felt careless. Practices that worked elsewhere clashed with a system where precision precedes trust. After nearly a decade of losses, Walmart exited the market. The lesson wasn’t that Germany is difficult. Far from the western world, inside Toyota factories, any worker can pull the andon cord - stopping the entire production line if they detect a defect. From a speed-first mindset, this looks inefficient. From a Japanese mindset, it’s essential. Reliability is not optimized at the end. This philosophy shaped Toyota’s global reputation: exceptional quality, deep trust, and extreme customer loyalty. In Japan, innovation that risks reliability is not progress - it is irresponsibility. Toyota didn’t scale despite this constraint. Back in India, when Tata Motors launched the Nano, it was positioned as the world’s cheapest car - a triumph of engineering frugality. Yet adoption disappointed. Not because Indians rejected affordability, but because frugality in India is not about cheapness. It is about maximizing resilience under uncertainty. Buyers evaluated durability, resale value, long-term risk, and social signaling. A product optimized purely for low cost felt fragile. What was intended as value was perceived as vulnerability. The Nano didn’t fail because it was too cheap. What These Stories Have in CommonAt first glance, these stories seem disconnected - different industries, different geographies, different outcomes. But beneath them is the same force at work. Each company collided with something invisible but immovable: a local decision logic that shaped what “good,” “safe,” and “valuable” meant before any product was evaluated. Culture didn’t influence perception at the margins. The easiest way to understand this is not as preference or identity, but as gravity. Think of every market as exerting a gravitational pull. Silicon Valley pulls products toward speed. These forces are not optional. You don’t negotiate with them, persuade them, or out-market them. You either design in alignment - or you burn energy fighting physics. When a product aligns with a market’s cultural gravity, distribution feels effortless. Each company encountered a cultural operating system - an invisible logic governing how people evaluate risk, trust, time, and value. And each outcome was determined by alignment or misalignment with that logic. These were not failures or successes of marketing. They were distribution outcomes shaped by cultural gravity. Before we dive into the operating systems of culture, it helps to anchor our understanding in the insight of one of management’s foundational thinkers.

This isn’t a clever aphorism. It’s a structural truth: if your assumptions about risk, trust, and value don’t align with the cultural logic of a market, no amount of strategy will get you adoption. Culture Is Not Identity. It Is Decision Logic Culture is often reduced to symbols: language, customs, aesthetics. For strategy, that definition is useless. What matters is culture as decision-making under uncertainty. Every market answers the same questions - but answers them differently:

These answers shape how products spread. Distribution is not neutral. A product does not scale because it is objectively superior. Four Cultural Operating Systems of ScaleThe opening stories map cleanly to four dominant cultural logics. Silicon Valley: Speed as a Moral GoodSpeed in Silicon Valley is not a tactic. Action is rewarded more than correctness. This produces an environment where:

The cultural constraint here is impatience. But that same constraint becomes a distribution advantage. Products optimized for speed benefit from rapid feedback loops, fast social proof, and capital markets that reward momentum over certainty. This is why many Silicon Valley–born products feel “unfinished” elsewhere. They are not poorly designed - they are overfit to a culture where speed substitutes for trust. Germany: Precision as Trust InfrastructureGermany runs on a different operating system. Here, precision is not pedantry. Correctness signals seriousness. German decision logic prioritizes:

The constraint is clear: speed without rigor destroys trust. This makes Germany a difficult market for products built on “launch fast, fix later” assumptions. But for companies that align with this logic, the reward is profound. Precision becomes a distribution advantage because once trust is established, switching costs are high, reputations compound slowly but powerfully, and products embed themselves deeply into workflows and institutions. In this context, slowness is not inefficiency. Japan: Reliability as a Social ContractIn Japan, reliability is not a feature. The social cost of failure is high. Japanese decision logic emphasizes:

Failure is reputational, not educational. This makes Japan hostile terrain for hype-driven launches. But for companies that adapt, reliability becomes an extraordinary distribution moat. Once trust is earned:

Innovation still exists - but it is subordinated to reliability. What outsiders see as resistance to change is actually a filtering mechanism. India: Frugality as Adaptive IntelligenceFrugality in India is often misunderstood as price sensitivity. That is a shallow reading. Frugality is not about cheapness. Indian decision logic reflects:

This produces buyers who ask:

The constraint is intolerance for waste. But frugality becomes a distribution advantage when respected. Products that succeed in India are modular, flexible, ROI-clear, and resilient. They scale through volume, not margin, and often travel well to other emerging markets. Frugality forces discipline. Strategic alignment with cultural logic doesn’t just help adoption externally - it shapes internal coherence around purpose and execution.

This insight reinforces what we’ve been seeing: when a product resonates with local cultural logic, the social and economic processes that carry it forward become more efficient - almost automatic. Why Startups Fail When They Fight Cultural GravityMost failed global expansions share the same root cause: The company’s internal optimization logic conflicts with the market’s cultural optimization logic. Speed-optimized teams enter precision-first markets. The result is rarely a dramatic rejection. Instead, it is slow non-adoption. Meetings happen. Momentum never arrives. From the inside, it feels like an execution failure. Culture as Distribution, Not Decoration Here is the strategic reframing that matters: Culture does not shape how your product is perceived. Distribution depends on:

These are cultural variables - not marketing ones. When culture aligns with your assumptions, growth feels effortless. From Constraint to AdvantageThe highest-performing global companies do not ask: “How do we adapt our product to this culture?” They ask: “How do we let this culture design our advantage?” Instead of fighting slowness, they turn thoroughness into trust. Culture becomes a force multiplier. A Founder’s Strategic PlaybookThis is not a checklist.

Culture Is StrategyThe final mistake is treating culture as something to overcome. Culture is the invisible architecture that determines:

When startups stop fighting this architecture and start designing with it, culture ceases to be a constraint. It becomes gravity. And gravity, once understood, is not an obstacle. It is what makes flight possible. - Before you build anything, make sure someone wants it enough to pay. I put together a free 7-day email course on revenue-first customer discovery — how to pull real buying intent from real conversations (without guessing, overbuilding, or hoping). If you’re a builder who wants clarity before code: © 2026 Startup-Side |

Pilots After Product Market Fit

Running new product pilots after stabilization can either signal strength or create confusion. This deep dive explains how to structure expl...

-

Crypto Breaking News posted: "Mikhail Fedorov, Ukraine's Deputy Prime Minister and the head of the country's Minist...

-

Techie.Buzz posted: " [ANN] Serverless Kubernetes Solution For Cloud-Native Apps by CTO.ai CTO.ai is a provider of deve...

-

kyungho0128 posted: "China's crackdown on Bitcoin (BTC) mining due to energy consumption concerns is widely regarded as...